From an essay "The Lost Landscape" byJoyce Carol Oates; I am akin to her father when it comes to gift-giving. I like to give someone a gift, but not because it's Christmas or a birthday:

When we were children my brother Robin and I had been astonished by our father's indifference to gifts. What meant so much to us, as children, meant literally nothing to him; Christmas and birthday presents for our father had to be opened by others (that is, by us} since Daddy thought so little of the ritual.

"Look, Daddy! This is for you" -- my brother and I would plead with our father, who might be reading the newspaper, or involved in one or another household chore, and would barely glance at us.

We'd thought our father so strange, not to care -- not to care about a present.

For children, even for teenagers, nothing seems quite so exciting as a wrapped present. For days beforehand my brother and I would speculate on the contents of packages beneath our Christmas tree, though our past experiences must surely have curbed our imaginations. But there was our father as indifferent to the excitement of gift-giving as he was to the gifts themselves {invariably shirts, neckties, socks}.

Of all writers it is Henry David Thoreau who most speaks to my father's temperament -- Beware of all enterprises that require new clothes.

And -- Simplify, simplify, simplify.

From my father I have inherited my ambivalence about gift-giving. I understand that it is an ancient and revered social ritual and that, in human relations, it is, or should be, a genuine expression of love, affection, admiration, respect; yet, through my life I have rarely felt more anxiety than I feel at the prospect of giving a gift. For how grateful one must be, for a present which {probably} isn't at all needed, or wanted; how can one reciprocate a gift, without making a social or personal blunder? Will my gift be wildly inappropriate, too costly/not costly enough? That gift-giving is so crucial to our society, the very wheel driving the capitalist-consumer economy, seems to me, as it seems to my father, unfortunate; the juggernaut of Christmas rolling around each year, overshadowing much else, invariably a season of apprehension and disappointment for many, seems particularly unfortunate. The very nicest "gifts" are those given spontaneously, without ritual or custom tied to a calendar, and those one can truly prize' the others, duly wrapped in expensive paper, part of a seasonal barrage of gifts, are likely to be dubious.

The gifts which I give to my parents now are more meaningful to Daddy than the perfunctory gifts of long ago -- these are books, records, subscriptions to magazines (Atlantic, Harper's, Hudson Review, Kenyon Review, Paris Review in which from time to time work of mine might appear}; of course I've given my parents copies of each of my books, of which several have been dedicated to them. {Daddy has joked that he's had to build a special bookcase in their living room, to accommodate my books.} They have an ongoing subscription to Ontario Review.

Literary Crushes/Grave Matters

Monday, October 8, 2018

Friday, March 9, 2018

JOHN LENNON CHRISTMAS CARD (RARE? SUPER-RARE? BEYOND-RARE?)

In those "London Life" days I wrote about above (Aug. 22 to early October, 1966), there were at least three tabloid-style weeklies about rock 'n roll -- I remember New Musical Express, Melody Maker, and Music Echo. We bought every issue. It was great to have so much to read about the music and musicians we loved. It was also a novelty; in the States we had had no such thing; Rolling Stone magazine didn't start until November of the following year.

(And, as for that, it has always sort of amazed me that on a lunch hour I walked into a rather old-fashioned pharmacy on Washington Avenue in Lansing and there, on the bottom rack of the magazines, was the very first issue of Rolling Stone -- how did it ever get to Michigan, I later wondered, and to Lansing, and to the last place in town you'd expect to find something so new, and which, naturally, I'd never heard of, but which, with a picture of John Lennon on the front, I had to have?)

In one or the other of those British magazines, a short article reported that John Lennon had designed a Christmas card for Oxfam (England's version of The Salvation Army), and that the cards would go on sale on such and such date (probably October 1st) at the headquarters of Oxfam's offices, and the address of this place was

provided. We got out our London A to Z book of maps; the place wasn't easy-to-find but we scouted it out ahead of the date the cards were to go on sale, noticing a sign on the door that listed the opening hour as 10AM.

At ten on the morning of the day the cards were to go on sale. Dennis and I were waiting outside the door.

I have a vague memory of there being some discussion amongst the two or three ladies there as to whether or not they were allowed to begin selling the cards. We said that it had been announced in a newspaper; we even had the paper with us, which we'd brought along to have the address, and we explained that we were from the states and had to return very soon, so we couldn't come back later after whatever the problem with whether or not the cards could go on sale was settled. I'm sure too that our faces and demeanors betrayed desperation, because we were desperate. We had to have some of those cards; our hearts would be broken if we walked out of there empty-handed. After further discussion amongst themselves, and with what seemed to be an amount of pity taken upon us, it was decided that they would sell us the couple boxes we each wanted.

At some point I wondered if these cards might be worth any money. I did a Google search on "John Lennon Oxfam Christmas Cards" and got some 77,600 hits; leave out the "Oxfam" and you'll get nearly five million hits. Of the Oxfam hits, every one of the many, many that I checked out was about a 1965 card design Lennon did for Oxfam, known as the "Yellow Fat Budgie" card. Over a period of time, I spent a lot of down-time at work searching through these google results, but could find not one single reference or picture of the cards Dennis and I had bought.

This led me to speculation. I imagined that final legal permission for the use of the card had not been procured, and that five minutes (or whatever) after Dennis and I walked out the door a phone call was received at Oxfam Headquarters from some barrister who announced that the cards must not be sold; indeed all stock on hand must be gathered for destruction. I fancy this as a screw-up amongst Beatle management (running amok as it often was, especially during this period), and some lazy-assed barrister who just didn't stay on top of things -- the note he or she'd made to legally assign Oxfam permission had been lost near the bottom of a stack of disorganized papers. I can not imagine the kindly John Lennon himself taking back permission for this charitable contribution; if you read a lot of books about the Beatles, as I have, you can well imagine that he was totally unaware of the screw-up; both their personal and their business lives were hectic beyond hectic.

I hope ... I really do ... that none of those two or three ladies who took pity on Dennis and me lost their jobs, or got their derrieres reamed out. "What are we going to do?" a worried Penelope might have said. Then, after a quick thought, "They're not going to count the boxes ... let's just keep it to ourselves. Here, Clarissa, take the money the boys paid and put it in the collection at next Sunday's services, so we don't have to account for it!"

Were Dennis and I the only ones in the whole wide world who owned one and more of these cards? If so, and the provenance could be established (simple enough; go to the British Library and locate the article that announced the cards, and then look at my innocent face), wouldn't one of those rabid collectors give me $100,000 for one? A million for one?

Well ... at least fifty bucks?

No, thanks, to any offers.

I don't remember, but there would have been ten or twelve cards in each box. I wonder who Dennis sent his to? (I can't ask him; my closest friend died in 1989). I wonder who I sent most of mine to? I wonder if any of the recipients saved theirs.

I saved two or three of mine as keepsakes. I had one framed about thirty years ago, and a year or so ago, I passed it on to someone I love who loves Lennon so much that, in emulation, he named his first born son Sean.

I came across another one amongst my papers about two years ago; I gave it to a co-worker named John who is way younger than me, and who delights me with his mastery of rock 'n roll trivia; indeed, for a birthday present, his mother -- herself an expert at rock trivia -- gave John a brick that is embedded in the plaza of The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland; it is inscribed with John's name and a designation as "Trivia King." What a cool mom!

(And, as for that, it has always sort of amazed me that on a lunch hour I walked into a rather old-fashioned pharmacy on Washington Avenue in Lansing and there, on the bottom rack of the magazines, was the very first issue of Rolling Stone -- how did it ever get to Michigan, I later wondered, and to Lansing, and to the last place in town you'd expect to find something so new, and which, naturally, I'd never heard of, but which, with a picture of John Lennon on the front, I had to have?)

In one or the other of those British magazines, a short article reported that John Lennon had designed a Christmas card for Oxfam (England's version of The Salvation Army), and that the cards would go on sale on such and such date (probably October 1st) at the headquarters of Oxfam's offices, and the address of this place was

provided. We got out our London A to Z book of maps; the place wasn't easy-to-find but we scouted it out ahead of the date the cards were to go on sale, noticing a sign on the door that listed the opening hour as 10AM.

At ten on the morning of the day the cards were to go on sale. Dennis and I were waiting outside the door.

I have a vague memory of there being some discussion amongst the two or three ladies there as to whether or not they were allowed to begin selling the cards. We said that it had been announced in a newspaper; we even had the paper with us, which we'd brought along to have the address, and we explained that we were from the states and had to return very soon, so we couldn't come back later after whatever the problem with whether or not the cards could go on sale was settled. I'm sure too that our faces and demeanors betrayed desperation, because we were desperate. We had to have some of those cards; our hearts would be broken if we walked out of there empty-handed. After further discussion amongst themselves, and with what seemed to be an amount of pity taken upon us, it was decided that they would sell us the couple boxes we each wanted.

***

At some point I wondered if these cards might be worth any money. I did a Google search on "John Lennon Oxfam Christmas Cards" and got some 77,600 hits; leave out the "Oxfam" and you'll get nearly five million hits. Of the Oxfam hits, every one of the many, many that I checked out was about a 1965 card design Lennon did for Oxfam, known as the "Yellow Fat Budgie" card. Over a period of time, I spent a lot of down-time at work searching through these google results, but could find not one single reference or picture of the cards Dennis and I had bought.

This led me to speculation. I imagined that final legal permission for the use of the card had not been procured, and that five minutes (or whatever) after Dennis and I walked out the door a phone call was received at Oxfam Headquarters from some barrister who announced that the cards must not be sold; indeed all stock on hand must be gathered for destruction. I fancy this as a screw-up amongst Beatle management (running amok as it often was, especially during this period), and some lazy-assed barrister who just didn't stay on top of things -- the note he or she'd made to legally assign Oxfam permission had been lost near the bottom of a stack of disorganized papers. I can not imagine the kindly John Lennon himself taking back permission for this charitable contribution; if you read a lot of books about the Beatles, as I have, you can well imagine that he was totally unaware of the screw-up; both their personal and their business lives were hectic beyond hectic.

I hope ... I really do ... that none of those two or three ladies who took pity on Dennis and me lost their jobs, or got their derrieres reamed out. "What are we going to do?" a worried Penelope might have said. Then, after a quick thought, "They're not going to count the boxes ... let's just keep it to ourselves. Here, Clarissa, take the money the boys paid and put it in the collection at next Sunday's services, so we don't have to account for it!"

Were Dennis and I the only ones in the whole wide world who owned one and more of these cards? If so, and the provenance could be established (simple enough; go to the British Library and locate the article that announced the cards, and then look at my innocent face), wouldn't one of those rabid collectors give me $100,000 for one? A million for one?

Well ... at least fifty bucks?

No, thanks, to any offers.

***

I don't remember, but there would have been ten or twelve cards in each box. I wonder who Dennis sent his to? (I can't ask him; my closest friend died in 1989). I wonder who I sent most of mine to? I wonder if any of the recipients saved theirs.

I saved two or three of mine as keepsakes. I had one framed about thirty years ago, and a year or so ago, I passed it on to someone I love who loves Lennon so much that, in emulation, he named his first born son Sean.

I came across another one amongst my papers about two years ago; I gave it to a co-worker named John who is way younger than me, and who delights me with his mastery of rock 'n roll trivia; indeed, for a birthday present, his mother -- herself an expert at rock trivia -- gave John a brick that is embedded in the plaza of The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland; it is inscribed with John's name and a designation as "Trivia King." What a cool mom!

|

| Detail copied on b/w copier; I colored the mistletoe berries with a red magic marker. |

It has occurred to me that I might send a copy of the card to Yoko Ono; she is known to have a vast amount of Lennon/Beatles material; maybe she has information about it, or would at least be interested in what I have. I will do that ... I will write Yoko a letter, She might answer. After all, when I read the excellent Jon Weiner biography of Lennon in 1984, I was so moved as to write a letter to Yoko, telling her how much I loved John Lennon, and expressing a wish that she would open a museum full of Lennon memoribilia, so that we who loved him could visit it and feel closer to him. I didn't write in a way that asked for a response, but she nevertheless was kind enough to send me a Christmas card that year; I framed it and treasure it.

And if I should run across another of those cards amongst my vast piles and files of papers, I could send it to Yoko if she doesn't have one, as seems likely. Then maybe I'd get another Christmas card from her!

LONDON LIFE

In 1959 I arrived at the small Muenchweiler Army Post in Germany, which comprised a Station Hospital (as opposed to a Field Hospital) and a Med Evac company -- about 300 troops total, and only about 30 patients in the 300-bed hospital). Having trained as a Medical Corpsman at Fort Sam Houston in Texas, I was lucky enough not just to be in a wonderful small town-setting in Germany, but also to be assigned as an Accounting Clerk in the Mess Hall of the hospital. My boss was a Warrant Officer named Phil Alden. He was a native of Texas who had married an English woman named Ella Renfield just after the war. Ella possessed an astonishingly beautiful soprano voice, had had the beginnings of a career in opera; her aspirations dwindled to a halt as a result of the actions of a man named Hitler.

Ella became so precious to me in so many ways, and I hope to write about her at greater length in a future post I'm planning about my Army days -- but this post is about London. Ella talked a lot about life in London, and it was certainly her influence that caused me to decide that I wanted to live in London someday.

I certainly didn't have a nest egg when I was discharged from the Army. Back in the states, working for Western Union, it took me five years before I had built up a stash large enough that I thought I could get myself settled in London; I felt certain that I could get a job with Western Union Telegraph Company there; I was a whiz at a teletype machine. (Upwards of a hundred words a minute! Not to brag, but sometimes people standing at the counter, who'd come in to send a telegram or a money order, would stare in amazement, often making a comment, as they watched my fingers fly over the three rows -- not four like a typewriter -- of teletype machine keys.)

I'd always supposed I would go to London by myself. About a year before I began making serious plans to go, I told my friend and apartment-mate Dennis in Lansing what I hoped to do. He was sort of my boyfriend until we realized that we made much better friends than we did boyfriends. He immediately -- this was in the boyfriend stage --wanted badly to go with me but when I told him I intended to go in a year or so, and he had no money to speak off, and I really couldn't see him making and saving enough by the time I intended to become, like Hemingway and Stein and T.S. Eliot and all those other cool people, an ex-pat, I said I thought it would be best for me to go alone as planned. I'm sure I cited an old Chinese proverb Phil Alden had impressed me with: He who travels alone travels further.

The time I planned to leave grew close, and then closer. One morning as Dennis was ironing a shirt before going to his job as a clerk in a record store, he asked me again if he could go with me. "Where're you going to get the money?" I asked. He pulled his copy of Gone with the Wind from his bookshelf; tucked within was a stash of cash, some $1000 dollars or so. I said I still didn't think it was a good idea ... I was going to London to make a new life. From overseas, I planned to write him and other friends and family beautiful letters. Re-aligning my dreams to include a fellow traveler would be, at best, uncomfortable.

Tears came to his eyes.

There was only one way I could deal with the sight of tears. Okay, he could go -- it was rash, but I would work it out somehow. (As will be revealed by the end of this post, his going with me turned out to be for the best.)

When I asked him how he'd saved so much money in so short a time, he said he'd helped himself to up to twenty-thirty bucks a day from the record store's till. The rich, in this case, got poorer, and the poor got richer.

***

So, when Dennis and I passed through London on our way from Paris to Dublin, staying eleven or twelve days, lodging in inexpensive hotels, moving from one to another when we came across a cheaper one, and spending a lot of time visiting an extremely charming man who was already past seventy, named Leo Welch, who was Ella's best friend. I had already met Leo, who lived on Red Lion Square, when I'd come to London in 1961, on one of my leaves from the Army, and when he'd come to Muenchweiler to visit Ella. I loved Leo. I also loved Leo's flat in London; just a bed-sitter really, but in a modern building, and with a bathroom and a small kitchen with, as Leo put it, all the "mod cons." Dreaming even then of living in London, I asked him if he would mind telling me how much per month his apartment cost. "Fifteen pounds," he said; about $42.00.

Dennis and I loved calling on Leo; his flat was in the West End near London's entertainment center. Leoe was clever and witty and fun; curious as to our comings and goings, curious about our generation; by our love of the Beatles. Leo was on a level,really, with my beloved Ella -- fascinating, fun, intelligent, friendly. He nicknamed Dennis "Babycham" because that was the name of a bottled slightly alcoholic drink Dennis brought to the flat one night when we were changing hotels and were invited to sleep on Leo's carpeted living room floor.

When we got back to London from Ireland, we got a room at the YMCA, but it was just a few days before we found our own place. The rent was shocking, nearly forty pounds a month, but, frankly, we'd checked out several places and this was the cheapest of them all. It was just a large room, with a double bed, a bathroom, and a hot plate for cooking; a couch; and a nice table with two chairs at the windows. It suited us alright; our diet consisted mainly of boiled potatoes with butter, and, for variety's sake, some version of eggs, as well as, when we were out and about, a lot of Wimpy burgers, and, when we really felt like splurging, an omelette at a sort of classy (for us) sit down restaurant. (A Wimpy Burger, sort of like a White Castle but tastier and larger, came with chips and cost about 75-cents!)

An inconvenience, and a surprising expense, was that to get hot water or heat for the hotplate, one had to put a shilling into a meter installed in the flat (as was the case in most other rented flats); it would provide heat for a certain amount of time; if you wanted to boil some potatoes or take a shower, you needed to make sure you had adequate shillings to buy adequate time on the meter. I could not imagine how many shillings you'd need for heat when winter came.

Our flat was far up in the Kilburn district, a good forty-five minute Tube ride from what we considered the West End, or central London.

When I told Leo how much we were paying he thought we were being ripped off, but we were settled in and, frankly, having learned how much apartments were going for, I'd had to come to have second thoughts about my ability to live alone in London. Dennis had, from the get-go, no intention of staying forever. I asked Leo how it was that his great and centrally located apartment cost him only 15 pounds a month, a fact which I'd used when strategizing my future in London. "Because I'm an old-age pensioner," he said.

Before we set out for Ireland, I'd gone to the main Western Union office in London and asked if they would give me a job; the nice man there, seemingly both amused and charmed at the novelty of a Yank applying for a job, thought they could. Right then and there he sent a telegram to the manager of the Western Union office in Lansing, asking for a character reference and so forth. Because it was late in the afternoon in London, and about eight a.m. in

Michigan, a quick response came by wire: I was said to have been a good employee except that I had not showed up for work after the settlement of the recent strike; he joked, however, that this must have happened because I was too far away for an easy commute.

I said to the Western Union man in London that I was going to Ireland for a couple weeks. He said he would send me particulars about employment in a letter which he would post to me care of American Express in Dublin:

Then, on instructions from the man at Western Union, I went to some sort of immigration office and said I wanted to get a work permit.

I was initially startled. One of my favorite poems to recite aloud was Oscar Wilde's "The Ballad of Reading Gaol" and it crossed my mind that I might be jailed -- or gaoled -- for having committed what must be, judging by my inquisitor's fierce disposition, a serious crime! Would I soon be a guy similar to the one in Wilde's poem?

By the time I got the following letter from Western Union, our cash stash had dwindled.

In those days you could buy a round-trip ticket, which we'd done because it cost barely more than a one-way, and you could just show up at the airport in Luxembourg on whatever day you wanted to use your return ticket.

We arrived at JFK Airport on Sunday, October 9th. Dennis bought a ticket for San Francisco to visit a friend. His flight was about noon and I went with him to the gate, as you were allowed to do in those days. My flight for Fort Wayne, Indiana, was late in the afternoon. Game 4 of the World Series was being broadcast all over the terminal on radios and television. I loathed all sports except basketball. (It is against the law to not love basketball if you are Hoosier-born.)

I felt alienated and lonely and lost and out of place. I was surrounded by idiots screaming and cheering and roaring. I didn't care that the Orioles were sweeping the Dodgers.

I took a seat in a sort of remote area, leaned forward, put my hand over my eyes, and wept.

I got a good job at Magnavox in Fort Wayne. Having no car, the only room I could find close to work was above a loud bar down the road from my job. I could walk to work.

A young black man and I were charged with inventorying every piece of property in the truly gigantic factory. The man who would oversee our work took us to look at a typing pool; I swear that in this gymnasium-sized room there were eight or nine rows of typists, all female, maybe 30 to a row. Jesus! One of my jobs would be to get the serial number, make, and model of each and every one of these typrwriters.

I could handle that.

My colleague was less easy to handle. He had a degree and I didn't, but we were making the same wage. He made a point a couple times a day of letting me know that he was seriously Christian. I brought a book to work to read during my breaks and lunch periods. It was a paperback of La Batarde, by Violette Leduc. One day he picked it up, examined its front and back, asked me what "La Batarde" meant, and then said, "Why would you want to read a piece of trash like that?"

I didn't even want to respond. Nothing he said interested me, and I supposed that nothing I cared about interested him. Much of every day was spent in a relatively small room with him. The situation hurt my brain.

I worked two weeks and now had enough money to put down towards a used VW Bug. I packed up my books and clothes and headed for Lansing. I crashed with two girls who had been my friends since they were Juniors in High School, and I was then 24. They used to tell their parents that they were going to stay at one or the other's overnight, and then they'd come and party all night with Dennis and me and whoever else was around, crashing on the floor. Hippie-dom was approaching!

I dropped in at the Western Union office. They were glad to see me and put me to work the next day.

I had dreamed of living in London. I'd tried, but I was now right back where I'd started. I was teletyping. Teletyping really really fast.

Ella became so precious to me in so many ways, and I hope to write about her at greater length in a future post I'm planning about my Army days -- but this post is about London. Ella talked a lot about life in London, and it was certainly her influence that caused me to decide that I wanted to live in London someday.

I certainly didn't have a nest egg when I was discharged from the Army. Back in the states, working for Western Union, it took me five years before I had built up a stash large enough that I thought I could get myself settled in London; I felt certain that I could get a job with Western Union Telegraph Company there; I was a whiz at a teletype machine. (Upwards of a hundred words a minute! Not to brag, but sometimes people standing at the counter, who'd come in to send a telegram or a money order, would stare in amazement, often making a comment, as they watched my fingers fly over the three rows -- not four like a typewriter -- of teletype machine keys.)

I'd always supposed I would go to London by myself. About a year before I began making serious plans to go, I told my friend and apartment-mate Dennis in Lansing what I hoped to do. He was sort of my boyfriend until we realized that we made much better friends than we did boyfriends. He immediately -- this was in the boyfriend stage --wanted badly to go with me but when I told him I intended to go in a year or so, and he had no money to speak off, and I really couldn't see him making and saving enough by the time I intended to become, like Hemingway and Stein and T.S. Eliot and all those other cool people, an ex-pat, I said I thought it would be best for me to go alone as planned. I'm sure I cited an old Chinese proverb Phil Alden had impressed me with: He who travels alone travels further.

The time I planned to leave grew close, and then closer. One morning as Dennis was ironing a shirt before going to his job as a clerk in a record store, he asked me again if he could go with me. "Where're you going to get the money?" I asked. He pulled his copy of Gone with the Wind from his bookshelf; tucked within was a stash of cash, some $1000 dollars or so. I said I still didn't think it was a good idea ... I was going to London to make a new life. From overseas, I planned to write him and other friends and family beautiful letters. Re-aligning my dreams to include a fellow traveler would be, at best, uncomfortable.

Tears came to his eyes.

There was only one way I could deal with the sight of tears. Okay, he could go -- it was rash, but I would work it out somehow. (As will be revealed by the end of this post, his going with me turned out to be for the best.)

When I asked him how he'd saved so much money in so short a time, he said he'd helped himself to up to twenty-thirty bucks a day from the record store's till. The rich, in this case, got poorer, and the poor got richer.

***

The Communication Workers of America, the union I was a member of, planned to call a strike on a certain day in July if certain conditions were not agreed to by Western Union. Most people didn't think a strike would really be called. There had been so many past threats, but never, my elder co-workers said, a strike. Dennis and I made our reservation to fly to Luxembourg for the day after the strike was to be called

So when a strike really was called, it didn't matter much to me; I'd made other plans. While my co-worers were picketing, Dennis and I were boarding the train in Lansing, bound for an overnight ride from Detroit to New York.

After a long day of walking around Manhattan, seeing the newly released movie of "Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf" -- all the while full of really really deep regrets that we were leaving the USA one day before Dylan's Tarantula would be on sale in bookstores -- we boarded an Icelandic Airlines plane that was headed for a stop in Reykjavik and then, as I wrote in my Irish Diary above, Luxembourg.

After a long day of walking around Manhattan, seeing the newly released movie of "Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf" -- all the while full of really really deep regrets that we were leaving the USA one day before Dylan's Tarantula would be on sale in bookstores -- we boarded an Icelandic Airlines plane that was headed for a stop in Reykjavik and then, as I wrote in my Irish Diary above, Luxembourg.

Before we'd reached New York, the strike had been settled. But for me there would be no turning back; not, at least, for now.

***

|

| The building that housed Leo's flat, which was perfectly situated on the ground floor corner below these signs. |

Dennis and I loved calling on Leo; his flat was in the West End near London's entertainment center. Leoe was clever and witty and fun; curious as to our comings and goings, curious about our generation; by our love of the Beatles. Leo was on a level,really, with my beloved Ella -- fascinating, fun, intelligent, friendly. He nicknamed Dennis "Babycham" because that was the name of a bottled slightly alcoholic drink Dennis brought to the flat one night when we were changing hotels and were invited to sleep on Leo's carpeted living room floor.

When we got back to London from Ireland, we got a room at the YMCA, but it was just a few days before we found our own place. The rent was shocking, nearly forty pounds a month, but, frankly, we'd checked out several places and this was the cheapest of them all. It was just a large room, with a double bed, a bathroom, and a hot plate for cooking; a couch; and a nice table with two chairs at the windows. It suited us alright; our diet consisted mainly of boiled potatoes with butter, and, for variety's sake, some version of eggs, as well as, when we were out and about, a lot of Wimpy burgers, and, when we really felt like splurging, an omelette at a sort of classy (for us) sit down restaurant. (A Wimpy Burger, sort of like a White Castle but tastier and larger, came with chips and cost about 75-cents!)

An inconvenience, and a surprising expense, was that to get hot water or heat for the hotplate, one had to put a shilling into a meter installed in the flat (as was the case in most other rented flats); it would provide heat for a certain amount of time; if you wanted to boil some potatoes or take a shower, you needed to make sure you had adequate shillings to buy adequate time on the meter. I could not imagine how many shillings you'd need for heat when winter came.

Our flat was far up in the Kilburn district, a good forty-five minute Tube ride from what we considered the West End, or central London.

|

| Our flat was on the 3rd floor; the one with the opened windows. |

When I told Leo how much we were paying he thought we were being ripped off, but we were settled in and, frankly, having learned how much apartments were going for, I'd had to come to have second thoughts about my ability to live alone in London. Dennis had, from the get-go, no intention of staying forever. I asked Leo how it was that his great and centrally located apartment cost him only 15 pounds a month, a fact which I'd used when strategizing my future in London. "Because I'm an old-age pensioner," he said.

Before we set out for Ireland, I'd gone to the main Western Union office in London and asked if they would give me a job; the nice man there, seemingly both amused and charmed at the novelty of a Yank applying for a job, thought they could. Right then and there he sent a telegram to the manager of the Western Union office in Lansing, asking for a character reference and so forth. Because it was late in the afternoon in London, and about eight a.m. in

Michigan, a quick response came by wire: I was said to have been a good employee except that I had not showed up for work after the settlement of the recent strike; he joked, however, that this must have happened because I was too far away for an easy commute.

I said to the Western Union man in London that I was going to Ireland for a couple weeks. He said he would send me particulars about employment in a letter which he would post to me care of American Express in Dublin:

When we returned to London from Ireland I went to Western Union and gave them the necessary details.

Then, on instructions from the man at Western Union, I went to some sort of immigration office and said I wanted to get a work permit.

There were about twenty people ahead of me in line, and then about twenty behind me. I finally, at one of the desks up front, faced a fifty-ish woman with poorly dyed red hair and a presumably permanently soured countenance. I said I wanted to apply for a work permit.

Wow! I'd arrived at the worst possible desk! This redhead went ballistic! Screaming at me so loud that every one in the large room was turning to look and listening in.

I was initially startled. One of my favorite poems to recite aloud was Oscar Wilde's "The Ballad of Reading Gaol" and it crossed my mind that I might be jailed -- or gaoled -- for having committed what must be, judging by my inquisitor's fierce disposition, a serious crime! Would I soon be a guy similar to the one in Wilde's poem?

I never saw a man who looked,

with such a wistful eye,

upon that little tent of blue,

which prisoners call the sky.

Who did I think I was, she shrilled? I had broken Her Majesty's laws when I'd passed through immigration claiming to be a tourist; had I been truthful and told them that I was going to look for work, I would have assuredly (her exact word) been sent back to Calais on the return ferry. "Why did you lie?" she shrieked!

I lied again, telling her that I'd had no intention of looking for work when I came ashore. She screamed some more. I said I'd just dropped in at the Western Union office to chat, and ended up thinking it would be fun to work in my field in a foreign country, and a man I spoke with there thought it could be arranged.

She screamed some more; it did seem I should perhaps feel embarrassed -- every one in the room had be staring at me, but I thought: what do I care? I'm never going to ever see a single one of these people again. It even occurred to me that if she wanted to turn red-faced with anger, it was her blood pressure, not mine.

I telephoned Western Union, explained my dilemma, and the head of personnel said he would do what he could to get me a work permit, and that I may have to leave the country to get it. I said I'd visit Amsterdam,pick up my work permit there, and re-enter Great Britain legally, and gave him Leo's address as a contact point.

Meanwhile, Dennis and I were having fun exploring the city. We walked and walked and walked, hanging out especially in book stores and record stores, visiting tourist sites, sitting in Russell Square, near Leo's, which had a concession stand, having what the Brits called a "cuppa," -- a cup of tea that was 4-cents, and reading from whatever paperback book each of us carried in our jacket pocket. (Amazingly, even tea in such a humble place was excellent; years later at the airport in Dublin I was dismayed to see that tea was served from gigantic urns, and then delighted to find it tasted great, better than anything in the States!) Occasionally we'd have a beer, which would be served warm, but the pubs -- open only at certain times of the day -- were cozy and comfortable places to have a rest and read a newspaper.

It would have been hard to be drunks in London, as we'd often been back in Michigan. Pubs were closed in the evenings; if one wanted a full night of drinking you had to join a private club; we could not afford the annual dues.

Some days we lazily spent in our flat, boiling potatoes, reading, and listening to rock 'n roll on Radio Caroline, a "pirate" radio station that operated on a ship anchored just outside the reach of the law of Great Britain's BBC monopoly. Radio Caroline was a blessing because stations licensed in England sucked. Sometimes one or two hours a week of rock 'n roll might be broadcast.

Being rock 'n roll nuts, it was thrilling to see, at the famous Marquee Club on Waldour Street, the earliest (best) version of The Moody Blues, who'd recorded the gigantic 1965 hit "Go Now" which we were crazy about.

And then, on September 23, 1966, we had tickets to see The Rolling Stones at Royal Albert Hall; I think the tickets cost about five bucks each. And, boy, Dennis and I could hardly get over how cool we were! The Stones! In London!

They were fronted by The Ike and Tina Turner Revue. Tina, wearing an amazing electric blue-sequined mini-skirted dress and matching electric blue 5-inch heels, was simply mesmerizing as she sang and danced and shimmied back and forth across the stage. As an encore they did their current great Phil Spector-produced hit "River Deep, Mountain High." Ike and (mostly) Tina were awesome. Every fiber of my being was filled with awe.

As for The Stones, this was the era of young girls -- and probably some boys -- screaming throughout the performance, so you couldn't really enjoy the music; indeed, you could hardly hear it. And Mick Jagger had not yet learned to "move like Jagger," -- I think he learned some moves from Tina, and have read that one of the managers of the Stones, Andrew Loog Oldham, who was gay, taught Mick how to swish. But despite the screams and despite Mick's boring stand-in-place dancing, the entire show was still a spectacle.

A reporter named Norris Drummond, who was reviewing "the pop world's social event of the year" for The New Musical Express, wrote: "Keith Richard was knocked to the ground, Mick was almost strangled, while Brian Jones and Bill Wyman took to their heels, followed by dozens of determined fans. Charlie Watts sat quietly behind his drums watching the scene."

Order was eventually restored over and over again.

Dennis and I returned to our cruising around, spending our money, being half-lazy, curious, fascinated by the city.

One day Dennis and I encountered a couple of our neighbor ladies on the 2nd floor landing, and they chatted us up. Somehow it came to their asking if we would mind saying how much we were paying for our flat. They were shocked, and both told us that their rents were considerably lower and their flats nicer than ours. "He's just charging you more because he thinks Americans have lots of money."

So now we were pissed, but also by now we had picked a date to get back to Luxembourg to fly to New York. We would take a ferry to Holland, see the sights in Amsterdam, pick up my work permit even if I'd never use it, and then entrain to Luxembourg.

On the last day that we would be paying our rent, we told the landlord that we were going to Amsterdam just for a long weekend. Lo! He played right into our hands! His eyes behind the thick lenses of his glasses lit up, bulged with greed, and he asked if we could bring him back whatever the allowed limit was of duty-free fine chocolates and cigars. We said we'd be glad to do him that favor. Later that day he brought us a list of what he wanted and fronted us a considerable amount of cash to pay for it.

The crook thought we were such nice boys.

The night before we abandoned the flat, we broke into the electric meter box and took out all the shillings we had deposited. Then, afraid that he might step into our apartment and discover our criminality, we were afraid he'd call the police and have us arrested at the ferry embarkation point, so we lay low at Leo's for four or five days before we actually took the train to Harwich where we caught the overnight ferry for Hook of Holland, and then a short train ride to Amsterdam.

I picked up my work permit at American Express. Like I said, I'd never use it but, for the bawling out I'd endured, I for damn sure wanted to see what it looked like.

In those days you could buy a round-trip ticket, which we'd done because it cost barely more than a one-way, and you could just show up at the airport in Luxembourg on whatever day you wanted to use your return ticket.

We arrived at JFK Airport on Sunday, October 9th. Dennis bought a ticket for San Francisco to visit a friend. His flight was about noon and I went with him to the gate, as you were allowed to do in those days. My flight for Fort Wayne, Indiana, was late in the afternoon. Game 4 of the World Series was being broadcast all over the terminal on radios and television. I loathed all sports except basketball. (It is against the law to not love basketball if you are Hoosier-born.)

I felt alienated and lonely and lost and out of place. I was surrounded by idiots screaming and cheering and roaring. I didn't care that the Orioles were sweeping the Dodgers.

I took a seat in a sort of remote area, leaned forward, put my hand over my eyes, and wept.

I got a good job at Magnavox in Fort Wayne. Having no car, the only room I could find close to work was above a loud bar down the road from my job. I could walk to work.

A young black man and I were charged with inventorying every piece of property in the truly gigantic factory. The man who would oversee our work took us to look at a typing pool; I swear that in this gymnasium-sized room there were eight or nine rows of typists, all female, maybe 30 to a row. Jesus! One of my jobs would be to get the serial number, make, and model of each and every one of these typrwriters.

I could handle that.

My colleague was less easy to handle. He had a degree and I didn't, but we were making the same wage. He made a point a couple times a day of letting me know that he was seriously Christian. I brought a book to work to read during my breaks and lunch periods. It was a paperback of La Batarde, by Violette Leduc. One day he picked it up, examined its front and back, asked me what "La Batarde" meant, and then said, "Why would you want to read a piece of trash like that?"

I didn't even want to respond. Nothing he said interested me, and I supposed that nothing I cared about interested him. Much of every day was spent in a relatively small room with him. The situation hurt my brain.

I worked two weeks and now had enough money to put down towards a used VW Bug. I packed up my books and clothes and headed for Lansing. I crashed with two girls who had been my friends since they were Juniors in High School, and I was then 24. They used to tell their parents that they were going to stay at one or the other's overnight, and then they'd come and party all night with Dennis and me and whoever else was around, crashing on the floor. Hippie-dom was approaching!

I dropped in at the Western Union office. They were glad to see me and put me to work the next day.

I had dreamed of living in London. I'd tried, but I was now right back where I'd started. I was teletyping. Teletyping really really fast.

Wednesday, January 10, 2018

Thursday, October 19, 2017

HAPPY BIRTHDAY, EDNA ST. VINCENT MILLAY - 2-22-1892 - 10-19-1950

|

| Photo: Carl Van Vecten |

Edna Millay was the first poet with whom I fell in love. I discovered her at 19 when I bought a paperback of her poems, and I would lay on my cot with its brown wool blanket, in a barracks in Germany, and read her lyrics and sonnets over and over, memorizing several of them. I had not been a good student during 12 years of schooling in Mentone, Indiana, but Edna Millay turned out to be an excellent teacher. Through paying attention to her, I began to notice her precise punctuation; she was like Dylan's Louise who makes it all "too concise and too clear," and I picked it up easily. My love for Millay has been constant for all these close-to-sixty years.

i couldn't pick a favorite sonnet, but if I could it might be XLVII from Fatal Interview:

Well, I have lost you; and I lost you fairly;

In my own way, and with my full consent.

Say what you will, kings in a tumbrel rarely

Went to their deaths more proud than this one went.

Some nights of apprehension and hot weeping

I will confess; but that's permitted me;

Day dried my eyes; I was not one for keeping

Rubbed in a cage a wing that would be free.

If I had loved you less or played you slyly

I might have held you for a summer more,

But at the cost of words I value highly,

And no such summer as the one before.

Should I outlive this anguish -- and men do --

I shall have only good to say of you.

|

| Photo: Walter Skold |

Thursday, June 22, 2017

Irish (and a little Luxembourg) Diary 1966

For Johnny, who was born in 1966 while I was in London;

posted on his birthday, October 14, 2017.

posted on his birthday, October 14, 2017.

Ettelbruck, Luxembourg - July 16, 1966

On the train from the

airport, when we want off, we are jammed in with those getting onto it. From outside a conductor slams shut the door. I am yelling "Raus! Raus!" which I think is German for "Out! Out!" Then the

people around us realize; one of them opens the door and shouts to the

conductor, who shouts toward the engine. I get off and turn around to see Dennis squeezing through.

We walk across the street and

into a hotel. We meet a man from Rotterdam who speaks English. He

makes inquiries about the price for us, and we book a room.

And now we have walked through the

town and are sitting in a famous hotel's cafe having coffee, and I'm

having a sausage sandwich. The sandwich is composed of many

one-to-two inch thin discs laid upon two good sized slices of well

buttered bread, some tomato and pickle on top. I like the way the

coffee is served. It comes in your own little china coffee maker.

In the top they put the coffee and water; the water drains into the

lower part and when it is finished draining you remove the top and

the bottom becomes the cup you drink from.

One of the bridges in

Luxembourg City is majestic. While walking around Thursday night we

happened onto it and decided to stay on through Friday and see the

city in daylight. We walked through the park which is in a valley

over which these old and new beautiful bridges span up and down; very scenic.

Lots of green. It's fun to watch the dogs – at our hotel was a

dog named Mac who begged at our breakfast. This morning I saved him

a bit of my roll but he refused it and later Monique told us he wants

only sugar cubes. The hotel room is good, roomy, and clean, and

Monique and the older couple there, whom I presumed to be her

parents, amused us. If they smile at you it makes you feel good.

On Thursday night we each had a filet mignon that was covered with a delicious sauce, and

french fried potatoes, and salad – no, no salad! - and a tomato

soup that had a liquor base, and green beans, and ice cream. I loved

it for only $3.00. On Friday night we had weiner schnitzel for less

than $2.00, but it was not good – I mean it was in itself tasty

enough and we enjoyed it, but it didn't taste like the good meals of

weiner schnitzel I had had in countless German restaurants when I was

a soldier.

We've gone to several bars;

we look for one with a jukebox; it's fun to see what English songs

happen to be on them, and also to listen to the foreign songs.

Yesterday we went into a record store and looked over all the

different record jackets. And I bought a pair of black sandals down

the street and a pair of sunglasses. Here today Dennis bought a pair

of sandals and a Harris tweed sports coat.

July

7, 1966 – Diekirch

We just arrived here by foot;

it is 5 kilos from Ettelbruck. I have a new rucksack that is jammed

with a hard bread loaf, a stick of sausage, two kinds of cheese, a

jar of pickles (the jar itself cost 3-cents), two oranges, a bottle of wine

and a package of what must be home-made potato chips; the latter was

given to me by the lady in the shop where we bought the food. We'll stop along the road on the way back and have our meal. The walking

is fun, but we must get more used to it as Dennis is getting a

blister and I think I may be getting one on my little toe, but

perhaps when we hike we should wear our shoes instead of new sandals.

Diekirch is a little smaller

than Ettelbruck, although it is the seat of the county which both are

in; the county is also called Diekirch. And here in this city is

made the Diekirch beer which is apparently the most popular in

Ettelbruck. All the beer has a better, more distinct taste than in

the U.S.A.

While walking around

Ettelbruck after my sausage sandwich yesterday afternoon we passed a

Famille de Pension – the

menu and prices posted outside looked good so after returning to our

hotel and cleaning up some we went back to this place. It was late

for dinner and we were the lone diners. But the waitress, Palmyra,

spoke excellent English, and had six weeks ago married an American

Airman. Palmyra jabbered and jabbered and we were there until 10:30

p.m. We had beef steak, french fries, salad, three beers, and two

coffees for only 162 francs or $3.24. Palmyra was very interesting,

showed us her scrapbook filled with pictures of the wedding and

honeymoon. And answered many questions we had about Luxembourg and

things we had seen. She confirmed that the people here have a low

regard for the Germans. I had wondered what had been Luxembourg's

fate in WWII. There was, Palmyra said, not a street which could be

looked upon without viewing great destruction; in Palmyra's own house

one could stand on the ground level and look up to see the sky. When

her parents came back after the war it was required that they have a

business – everyone was required to have some sort of business in

order, I guess, to get some sort of an economy

moving again. So her family opened this room and boarding business

and today they still have their very first customer – a Germany

from just over the border. She showed us some of their guest rooms

on the upper floor; they were beautiful and spotlessly clean as well.

Her father had a Chow-Chow dog with the cutest face and we asked her

if we could be introduced to the dog. So when her father returned

from a bar where he had gone to get the winning Germany lottery

numbers off the television, he brought the dog to us. His name was

Mickey. Palmyra was terrified that he would leave one hair in the

dining room.

I asked Palmyra about General

Patton and she said, “He is a god to us.” His forces liberated

the city in 1944 and he was, after the war, killed in Luxembourg in a

jeep accident.

Since

we were not pleased with out hotel room across from the bahnhof

Palmyra told us to come in the morning and take one of her rooms; we

checked out then this morning but we had overslept; it was past noon

when we arrived at Famille de Pension,

and she, worried that we'd not come since we had

said morning, had let our room to someone else. But we walked down

the street and got a nice, bright looking room above a beer room. It

seems that almost every building houses not only someone's home but

also a beer hall

or a hotel or a restaurant or all combined; I suppose this is a

result of the days when every building was required to house a

business.

After

leaving Famille de Pension

last night we went into a bar in which we had spotted a jukebox on

our afternoon walk. The big song to hear here was “Long, Long

While” by the Rolling Stones, which, on this side of the ocean, is

the flip side of “Paint It Black”. After we'd been there a while

and Dennis was in the toilet, the youngest waitress came and sat

beside me, saying, “Excuse me.” And there she sat talking with

us until the place closed at one a.m. … sat with us except when one

of the local boys asked her to dance. She was not so interesting,

except inasmuch as any foreign person being friendly to you is

interesting. I spoke almost as much German to her as English, and

she understood me fine; I had been having trouble making myself

understood. This cafe was run by this girl's mother and two of her

sisters. This girl claimed her name was Baby. We witnesses

a very funny incident: One of the local men asked of one of Baby's

sisters at the bar if she were, as Baby put it, “a girl for money.”

The mother grabbed one arm and one ear, the insulted sister grabbed

the other arm and the other ear; there was much shouting and they led

the man quickly to the door where they farewelled him with a loud

slap on the face.

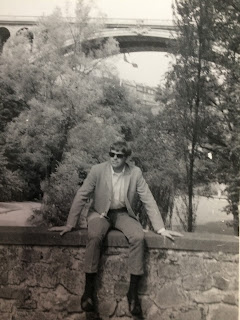

And now we have rested

enough. Dennis Little just snapped a picture of me writing, and we

must start back to Ettelbruck.

Paris, July 8 , 1966

I didn't keep up my diary while in Paris, but we did pose in our hotel room's window for pictures:

|

| Farm boy from outside Williamston, Michigan |

Nor did I keep my diary while we were in London camping on the floor of a friend before taking the train out of Euston Station for Holyhead in Wales where we caught a ferry for Ireland.

Dublin, August 6, 1966

Dublin, August 6, 1966

So I've gone all this time

without writing. I didn't intend to ignore my diary but in Paris and

London there are so many impressions I wouldn't have known how to

begin. But Dublin is a smaller and quieter place and we are heading

for even smaller and quieter places. We left London last night at

11:30; the seats on the train to Holyhead were terribly

uncomfortable; I slept but seemed to wake every five minutes and

change my position. The ferry was comfortable; in fact it was almost

like a nice chair in a living room and I slept at least three hours

of the four hour crossing. We landed at Dun Loaghaire at about 10:30

this morning. A guidebook we

have describes Dublin as a beautiful

city and as far as I've seen it couldn't be less accurate; I don't

like it at all, and if all of Ireland is similar to it I'll leave

quicker than planned. First of all, it is the dirtiest city I've

ever been in – there is litter all over the sidewalks, a bad odor

almost everywhere, and those openings beneath sidewalks covered with

gratings are usually piled with a foot or more of trash. Give me the

bright cleanliness of Holland or Luxembourg! The people here seem

wretchedly poor. We had a long walk through a residential area,

composed of large brick apartment buildings, each window covered

with tattered and dirty lace curtains – or so it seemed. Children

played on the sidewalks and they were filthy, their clothes little

more than rags. On the main streets there are girls soliciting funds

for some charity – you give coins and they stick a little badge on

your lapel. Two nuns were standing at either side of an entrance to

some building with tin cups held out. A little girl tonight begging

us for six pence because she hadn't bus fare home. Such poverty upsets me. All those people making donations on the street probably have poorly

clothed children in their families. And the church probably has more

money than any other institution.

|

| Dennis Little at Dun Laoghaire landing dock; that's a torn spot on the photo, not something white he's holding. |

see. From the Frommer's guide we used, and which I still have, I can identify the guesthouse we stayed in: The White House Hotel at 62 Amiens Street. It was fifty yards from the railway station. If we had happened to wander whatever which way there's no telling what sorts of neighborhoods we passed through.]

August

7, 1966

A better day as far as sights

go. But it started off in our hotel where we were served a lousy

breakfast. Dennis couldn't eat his except the egg; I managed to eat

the bacon but left the sausage which was not tasteless but of a very

bad taste. But the hotel is cheap and we should have expected this.

The

single reason I wanted to stop over in Dublin was to go to Dun

Loaghaire, to a place beyond Dun Loaghaire actually, called Sandy

Cove, to visit a James Joyce museum. So out on the street this

morning the newspapers informed us that the busses were not running –

a strike. So I asked directions of a man and we began walking the 7

miles to Sandy Cove. We would begin hitchhiking when we were out of

Dublin but just as we passed a house where Oscar Wilde had lived,

a Volkswagen stopped and the driver shouted that we could have a

lift. I crawled in back with his two children; Dennis sat up front.

“You must be a couple of Joyce disciples,” he said. Yes, we

were. So he began talking a storm; he obviously did not approve of

Joyce's picture of Dublin (Ulysses

is banned in Eire!), and he defended the actual character of a man

whom Joyce, according to our host, had maligned in his novel. He was

a good friend of this man's (Gogarthy?) son. Our driver was

obviously very religious; he made the sign of the cross often,

presumably every time we passed a church, so it is easy to see why

he'd knock Joyce.

August 8, 1966

I

was writing in a pub last night and it became so crowded that I

stopped in order to watch the people. But I should add to yesterday

that we were let off two miles from our destination and we walked

along the coast which is beautiful – many places they were swimming

and the sun was bright. We visited Martello Tower, an old tower on

the coast in which Joyce once lived with two friends – it is now a

museum in his memory, housing photos, original manuscripts and

letters, and various items

which belonged to Joyce. Returned on train.

We

began this morning in Dublin trying to rent a bike but there was a

rush on them because of a bus strike so we began hitchhiking. While

still in Dublin a very pretty and young teacher picked us up in a

tiny Morris and took us past Dun Loaghaire. Then a man in a Jaguar

sedan took us quite a distance, as far as Enniskerry I believe. I

told Mother in a letter from London that hitchhiking was “safe”

over here but this man's driving was hardly safe. Then we began

walking along a mountain, going up and around it. We were on a

less-travelled road and we walked for nearly four miles for our next

ride which was then only a mile long! We walked over a mile more and

were picked up and brought to within a mile of Glendalough, our

destination. We were too tired to look at the nearby ruins of an

ancient monastery this evening so we walked back a mile to this place

where we have a nice room for the night. We bought twice as much

groceries as we needed and had our supper in the lawn – we were

hungry as we hadn't eaten since Dublin. We'll look at the ruins in

the morning and then try to make Kilkenny by tomorrow evening –

probably won't be so lucky but it doesn't matter – wherever we are

in the evening is where well spend the night. As for tonight, we're

tired and though it's only 8:30 we're going to sleep.

Rathdrum,

August 9, 1966

This

is a beautiful little town, apparently about the size of Mentone. We

are having high tea – a pot of tea, 4 cups each, several slices of

bread with butter and strawberry jam, and a cupcake each. But getting

here was all hiking – not one of the few cars which passed stopped

for us, and at times it was pouring down rain. We have come only

seven miles from Larogh! But the country-side is beautiful, not quite

mountains, but very close. Very green; cute little farms along the

road – really the nicest scenes I've seen. We rested half way here

at a tiny store along the way – the lady was friendly and would

have got us a ride to Rathdrum with the bread man except on Tuesdays

he goes another way! We mailed our letters with her little post

office, bought an ice cream bar (3 pence) and a banana (5 pence),

then came on our way.

The

worse of all this rain is that we didn't get to leave Lilac Cottage

until noon and we decided to get started on our journey rather than

back-track a mile to see the ruins. So we saw only what we saw last

evening – the tower, which is almost perfect after over 1000 years.

And we also trudged a steep hill and saw the St. Kevin's Church in

use today.

We

were served a good breakfast this morning, started off with crushed

grapefruit. When we went out on the road and looked beyond us the

hill tops were half hidden in fog – it really is one beautiful

scene after another!

As

soon as we got into town here we went to a “drapery” shop to

purchase raincoats. The shop had none large enough for us but the

two women running it were friendly and we talked for fifteen minutes.

They laughed at my Irish name, thought Indiana was near Texas, and

that Chicago was not hot or cold but just windy. At the third shop we

went into they had our size and we bought thin plastic raincoats for

70-cents each. They were regularly 76-cents but were on sale!

Enough

– we'll try to get to Arklow, on the sea, before dark.

Arklow

We

made it; our luck changed. We left Rathdrum around six and three

rather quickly gotten rides put us here by seven. And the sun even

began shining this evening. This is a beautiful seacoast city of, I

would guess, seven or eight thousand. We got a clean bed and

breakfast for a pound, then went out for a walk – first down a row

of sweet little residential houses all cement with brightly colored

frames for doors and windows, down to the sea, then up along a

“river” which is really just a stretch of backwater from the sea.

From a bridge across it you can look northwest and see hills, green,

green hills, as far as the eye can see – Ireland, so far, has been

beautiful in the countryside – I couldn't even begin to make a

picture in words that would convey to anyone how beautiful the

scenery is – to be walking along a country road lined with trees

and a stone fence, to look down into a valley and see a river running

through it, and a footbridge crossing the river, then to look up and

see an infinity of green hills, to see clear to the top of some of

these hills where there are neatly divided and cultivated plots. To

stop at a country store and compare it to a supermarket – one of

these stores usually serves as a post office as well, and they sell

mainly only those things which the farmer can't get for himself from

his own land.

After

getting back to the bridge we walked up and then back down Main

Street, looking in the shop windows, and ending up in an upstairs

restaurant where I had a bowl of good oxtail soup with bread and

butter, and a large pot of tea for 30-cents.

Coming

into our guest house, called Elsinore, the hostess invited us into

her living room where we chatted with her and a friend of hers, Mary

Redmond, who lives on the edge of town. This was our largest taste of

Irish hospitality. They were immensely entertaining, witty,

broad-minded. They don't like the President of Ireland –

particularly they dislike the recently enforced requirement that

Gaelic be the official language.

After

our chatting the hostess served delicious coffee and toast; I then

had my first bath since we left England, feel clean, and tired and

ready to sleep

Kilkenny,

August 10, 1966

Often

during the day we didn't expect to reach this far by dark. But

despite the fact that we waited so long for rides it turned out that

we got some good ones. Quite a day it was, beginning with a good

breakfast at Elsinore; then we stood outside Arklow for an hour

before two boys from Bristol, England, in a Gazelle convertible, gave

us a lift. At Gorey they were heading over secondary roads to

Courtown on the sea; we preferred to stay on the main road south so

they let us out. We walked a short distance, heading out of town,

when I discovered that I'd left my camera in their car. My heart was

broken. Dennis said, “What do you want to do?” and I said, “I

want to cry” All I could think of was all the pictures we'd taken

which were still in the camera, and all the pictures of the rest of

the trip we wouldn't now be able to take.

We

decided to turn around and head for Courtown ourselves, hoping to

find the Gazelle there, though it really seemed doubtful we could get

a lift on that road. Luck! A doctor from Dublin stopped for us. As

soon as I told him my dilemma he accelerated and, sure enough, there

on the street, the green convertible was parked. I stayed at their

car and Dennis went to the beach to look for them. They returned to

the car before Dennis, and my camera was again in my hands. More

luck: They were disappointed with Courtown and had decided to get

back on the main road and drive further south, so they gave us

another lift, this time to Enniscorthy, where our route to Kilkenny

split from theirs to Wexford. As it turned out we left them in

Enniscorthy with a broken down car – something suddenly gone wrong

with the gearbox. Outside of town we jumped into a wagon pulled by a

tractor which took us four miles. Then a man delivering bathroom

fixtures took us to within one mile of Clonroche. We thumbed for an

hour and eventually walked into Clonroche, a tiny place where we

couldn’t even find a place to have tea. And we waited over an hour

for the next lift; a woman with her two daughters took us to the

junction one mile north of New Ross, which, incidentally, is where

President Kennedy visited his relatives on his trip to Ireland. From

there a man brought us clear to Kilkenny. He was very talkative and

friendly and stopped a few times along the route to allow us to get

out and see the view. One vista was especially beautiful – far

below in the green valley was a river and in the river were some

islands. And this scene was framed by the trees right in front of us

so that we had to stand at a certain place to see.

In

Kilkenny we first had soup, bread, and tea, then got a room for only

15 shillings each; the landlady possesses a subtle wit, very friendly

and amusing. Then we went to 35 Friary Street, the address of my

pen-pal, Flo Brennan; we’ve not corresponded since ’60 or ’61.

No one was home so we went to a pub a few doors down and had two

beers. The bartender told us that Flo still lives there with her

mother, and that she works in a “drapery” shop on the main street

so we’ll be sure to see her tomorrow.

August

11, 1966

After

breakfast we set off down High Street stopping at each “drapery”

shop asking if they knew Flo Brennan. Someone at the third one knew

her and said she was married, had two children, and lived in

Tipperary. We knocked again at 35 Friary; no response. In the

grocery store next door the lady confirmed that Flo was married and

she said she’d tell Mrs. Brennan we’d called, and that we should

try later.

Next

we went to what is called the “Design Center,” – a place where

people do exactly what the name says. In laboratories and studios

they design various items and they sell these designs to factories

where the item is manufactured and then marketed. This center is

semi-government sponsored and its purpose is to design goods mainly

which can be exported, thus strengthening Ireland’s place in the

Common Market. The items were beautiful, made of marble, of silver,

of wood, or of various fabrics; some things were for sale, one of

which was a silver ring, very unusually designed. It thought it was

beautiful and bought it for the amazingly low price of about $9.00.

The lady was very nice and took time to answer our questions and tell

us such things as that the building they are housed in was originally

the stables for the Kilkenny Castle across the street.

Later

we went to the castle, a huge grey building that is beautiful from

certain points, such as from the bridge on the Nore River behind it.

The inside was not much to see – a number of empty, dark, dreary

rooms really, the same as all old empty buildings. But they are

going to put the Castle to use by putting in an art gallery and also

making some areas into studios to be rented to artists.

We

visited also St. Canice Cathedral, a 13th

century Gothic monstrosity – Dennis loves such things. The yard

around was full of graves and a strange assortment of markers. As

well, the inside of the church was full of tombs and inscriptions, in

remembrance of such and such “dearly beloved” person. I thought

it very eerie. The most interesting fact in the Cathedral’s

history is that during an English occupation, Cromwell’s men

desecrated it; among other things, his men used the baptismal font as

a trough for the watering of their horses.

|

| St. Canice Cathedral; Kilkenny |

At

about eight tonight we knocked again at 35 Friary. Mrs. Brennan

answered and welcomed us. In the living room we met Flo and her

sister, Rosemary! The grocery lady had told Mrs. Brennan about us.

Mrs. Brennan then telephoned Rosemary, who lives 18 miles away, and

Rosemary drove and collected Flo, who lives 35 miles away and has no

phone. So all were there to meet us, including a batch of children.

Flo has two girls with Gaelic names – the oldest one is Maeve, the

youngest is, Aoife. Flo is as pretty as the several pictures I was

sent over the years, lovely blue eyes, and a wonderful smile.

Rosemary is also good-looking, wearing thick glasses, and clever and

really really funny, always something funny to remark upon. Dennis

and I like them both so much. They have poise and such friendliness.

Rosemary has four children. Mrs. Brennan is friendly, too, and we

were served high tea and, later, coffee. I found out why I like

their instant coffee: it is made with milk instead of water, very

good. After a while a girl of about 28, named Bridey, came home. It

is she who works in a “drapery” shop and she makes her home with

Mrs. Brennan. She is also Flo’s long-time best friend. She, too,

is fun and friendly. Foreigners seem to have so much more fun

together than do Americans; it’s fun to be with them – they seem

to have no petty ideas or prejudices, are completely content to

merely have a good time among themselves.

We

intended to leave Kilkenny tomorrow but Rosemary was very anxious to

take us pub-crawling tomorrow night so we willingly extended our

stay. Flo is staying overnight and tomorrow we are having dinner

[lunch] at 35 Friary and then are being driven to wherever we’d

like to go in the countryside.

I

wish I could say in words how wonderful and interesting these people

are. Everyone is equal, no-one is a show-off, and everyone loves to

laugh. We Americans, especially me, could learn so much from them.

But perhaps it’s some quality that can’t be explained and I

shouldn’t even try.

August

13, 1966

We

lunched yesterday at one o’clock with Mrs. Brennan, Flo, and Bridey

Dunne. We had just had our usual big breakfast 3 hours before and

were afraid we’d have no appetite, but the food was good and we

stuffed ourselves on cod, boiled potatoes with a white gravy, peas,

and a delicious dessert made up of custard drowned in canned pear

juice and topped with a couple halves of canned pears.

Then

we set off in Flo’s Fiat to visit ruins in the countryside. Our

first stop was at an ancient Cistercian Abbey. The sun was so warm,

the grass so thick and green, and the Abbey is a gorgeous place. I

don’t know much about architectural styles – if you say Georgian

to me I’ll know what you mean; if you say Gothic I’ll know what

you mean, but if you say anything else to me I probably won’t know

what you’re talking about. And I don’t know what this Abbey was

in architectural descriptions, but it was beautiful to me and I’m

hardly ever impressed by such things. The tower was still intact and

we climbed to the top via a narrow winding inside-stairs. Up there,

Flo, who stayed down, said we were little specks. The Abbey was

built around a courtyard and between this yard and the buildings was

this cathedral window pattern of what I surely shouldn’t call a

fence of archways. Whatever I should call it, the courtyard was

enclosed by these designs shaped like a cathedral window, perhaps ten

feet high, and four or five feet wide on the ground. The Cistercian

order, like the Trappists, have a vow to remain silent and maintain a minimum of

contact with the world outside their Abbey. This place is officially

called the Jerpoint Abbey; it was founded in 1158, and suppressed in

1541.

Then

we stopped at a pub along the road where Dennis and I had a half-pint

and Flo and her daughter Maeve had a form of apple cider. If you

order apple cider here you would be served an alcoholic drink, but

they had some other product based on apple cider. Later in the

evening Flo asked for a Bitter Lemon in a tavern – in the States

this would be an alcoholic drink; here it is not.

But

after our afternoon refreshments we went on to a place called

Burnchurch – the name of the ruins of a castle inhabited in the

13th

century by a family of Fitzgeralds; across the road were four or five

Fitzgeralds buried! But this place was not beautiful, just

interesting. Again Dennis and I went up narrow dark stairs to the

top – the passageways and nooks are fascinating. All that is left

of this castle though are two sections, both about 100 feet high, and

about thirty feet from each other.

After

returning to Kilkenny and having supper with Mrs. Brennan we went

with Rosemary and Bridey to a nearby town called Freshford where

Rosemary had to pick up some pork – her husband, Paschal, is a

victualer – a butcher – in Johnstown, another small town 18 miles

from Kilkenny. But the pork wasn’t ready so we headed back to

Kilkenny to collect Flo. One of Rosemary’s daughters, named

Jacqueline after President Kennedy’s wife, is a cute little six or

maybe just five year old – she knows she’s cute and is really a

flirt! I played games with her and one of these games was that I

would imitate her facial expressions and I was amazed at how much of

an actress she is. I told Rosemary that she’d become a great

actress, no doubt.

We

first went to a county bar where a girl was badly playing the piano;

then to a place on High Street called Jug of Punch, owned by the

Clancy Brothers, who are folk singers with some repute in America.